“Marie, why don’t you read aloud this section on Pearl Harbor?”

“Marie, why don’t you read aloud this section on Pearl Harbor?”

I froze.

I was in my 7th-grade history class and it was the very first time in my K–12 education in the U.S. that I had read about Japanese people. I felt utterly ashamed. Singled out in a sea of white faces in the class, I felt like we were back in World War II–like I was the enemy. If this was what it felt like for people like me to be featured in classroom materials, I never wanted it to happen again.

In the years that followed, I read about or watched Asian characters who spoke “Ching Chong” English, who served as sidekicks, who were only good at math, and who were exotic and submissive, among other harmful, stereotyped depictions.

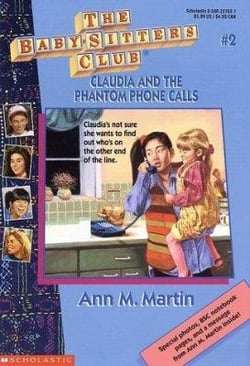

There was one character I met, though, who both understood me and allowed me to expand my imagination about who I could become. This character was The Baby-Sitters Club’s Claudia Kishi, a Japanese-American who didn’t like sushi and who had a special relationship with her grandmother—just like me! She was also stylish, artsy, outspoken, and effortlessly cool. She wasn’t perfect, but she was whole, and she made me believe that I was worth taking up space in this country where I often felt like I didn’t belong.

about who I could become. This character was The Baby-Sitters Club’s Claudia Kishi, a Japanese-American who didn’t like sushi and who had a special relationship with her grandmother—just like me! She was also stylish, artsy, outspoken, and effortlessly cool. She wasn’t perfect, but she was whole, and she made me believe that I was worth taking up space in this country where I often felt like I didn’t belong.

Having seen so few affirming, empowering representations of my own identity in the literature and textbooks I read during my own educational experience, I am passionate about our work at ANet to reflect the diverse identities of our students on our assessments. I know firsthand the pain of having our identities being reduced to a single dimension as well as the joy of seeing the fullness of our identities being shared with the world.

No student should feel dehumanized and devalued because they are wholly excluded from or grossly misrepresented in mainstream narratives. All students—especially students with marginalized identities—should feel affirmed and empowered in what they read.

To make this aspiration a reality, one tangible area of the progress we have made at ANet over the past several years is to increase racial representation across our assessment texts.

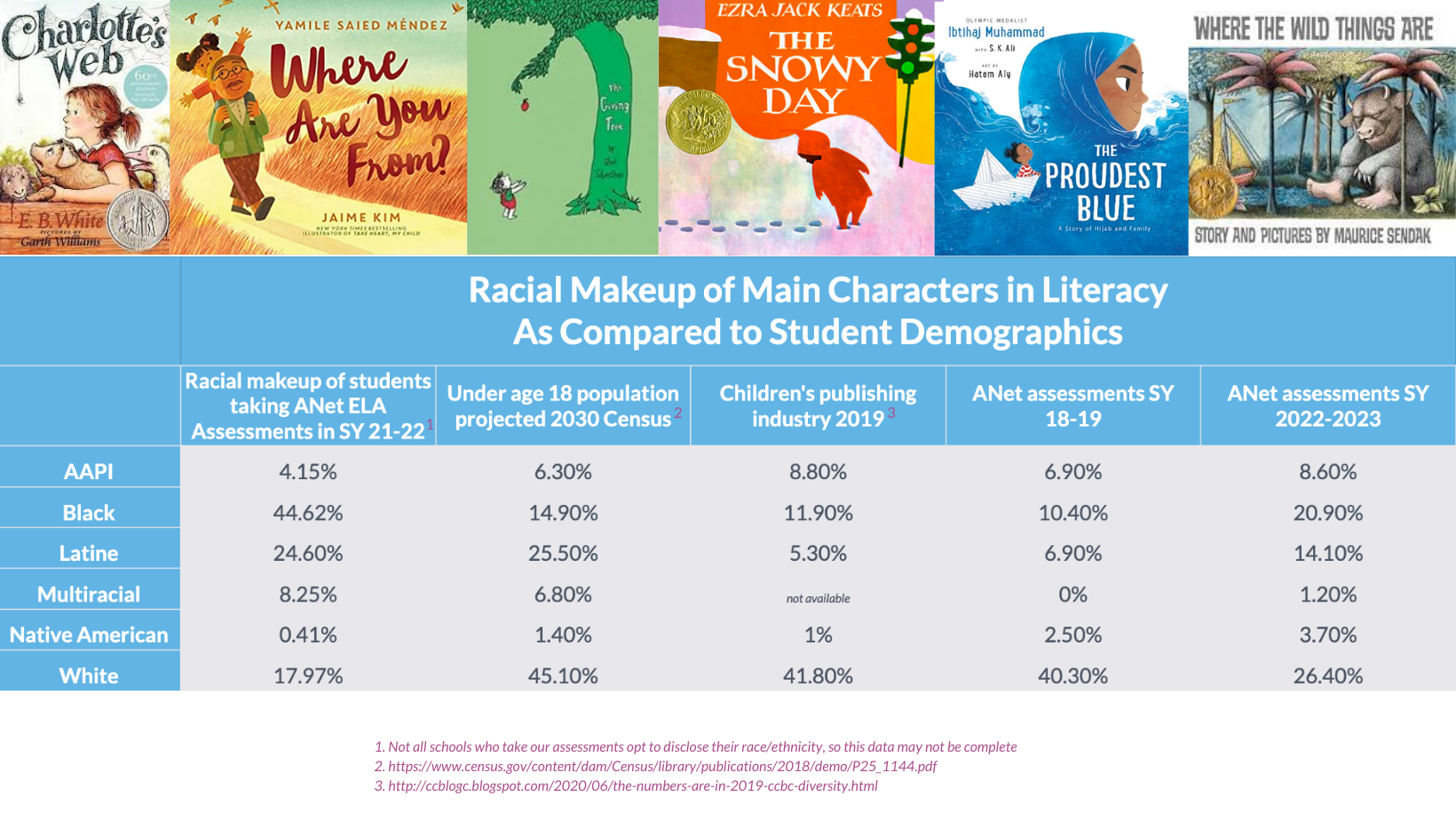

In 2018, ANet set forth a plan to better center on characters of color in our assessments based on a combination of student demographic data of ANet partners and Census data on the “under 18” population. Since then, we have been making steady improvements, as you can see from the chart below which shows the racial makeup of main characters in our assessment texts over time in the context of ANet partner schools, the Census, and the overall children’s publishing industry data:

As you can see from the children’s publishing industry column, there is already an abundance of stories that center on white characters. Because of this, white children have been and are able to see many facets of their identities represented in the literature that they read. We simply wish the same to be true for our students of color.

While we are proud of our work to increase racial representation despite the state of the children’s publishing industry, we know that we can continue to elevate stories about and by people of color, and we need to continue representing a broad spectrum of identities like gender, disability, religion, and socioeconomic status, among others. We have also renewed our commitment to not simply consider the number of texts that reflect these identities, but also focus on the types of stories that are being told and be thoughtful about the messages that students, especially marginalized students, are receiving.

For example, we strive to include a balance of informational and literary texts about both exceptional and “ordinary” people of color. Exceptional, such as the Navajo code talkers who were invaluable assets to the American army during WWII, or Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first Black woman in America to earn a medical degree. But also ordinary, everyday people of color such as the fictional characters Lupe Medrano, who becomes a champion marble player through hard work and dedication in The Marble Champ from Gary Soto’s anthology of short stories, Baseball in April, or Mindy Kim, who is nervous about running for class president in Lyla Lee’s Mindy Kim, Class President.

ANet wants to ensure that students are not just seeing people of color represented in texts about struggle and oppression or in stories where we need to be flawless, heroic, or exceptional; people of color deserve to be three-dimensional and have a voice in every sphere of life.

We know that assessment texts are a drop in the bucket of what students read across the year in school and at home, but we hope that our work can help normalize not only the inclusion of but also the wide-ranging and nuanced representations of various facets and intersections, of identities that students hold. We are eager and excited to continue this work and our own journey toward becoming an anti-racist, anti-oppressive organization that seeks to lift up the voices of people of color and enable them to share their own authentic stories.

This blog is a follow up to Marie Kodama and Snow Li’s original piece from June 2015, What students read matters.